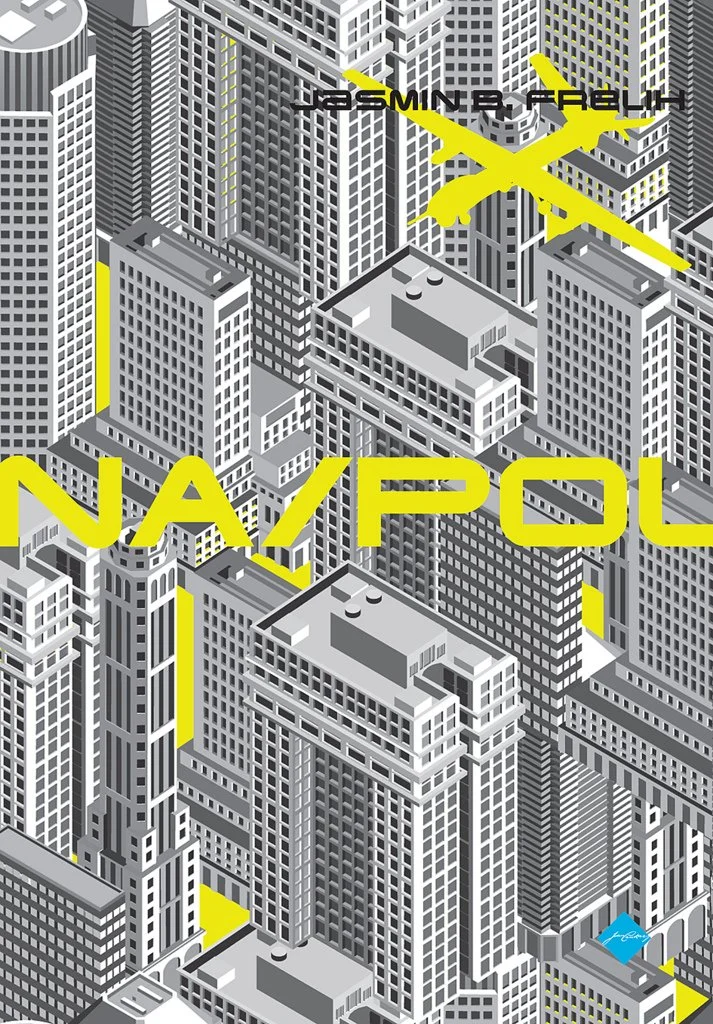

IN / HALF

“They’ll love you. They don’t want to punish you with that. Look at them, how they love. Look at their love. Nobody deserves anything. They will love you for free.”

IN / HALF

Oneworld, London, 2018

translated by Jason Blake

pp. 350

The world of the novel In/Half is a cut up world. A world without commons. Communication is made impossible, information is in fragments. Everyone is forced to think the world alone.

Evan is setting up a play in the Far East, while trying to close the rift dripping with the memory of his lost love. If you ever ate pancakes filled with chocolate cream, you will know how difficult it is to keep your hands clean.

Kras lost the election and is now slowly losing control over his family. Because he helped create a dangerous world, this worries him. On his fiftieth birthday, nobody gives him anything nice.

Zoja was made famous by poetry in the Far West. Fame no longer brings the benefits of civilization, only the attention of people. People who want to change things, people who want to destroy things, and people who do not want anything.

Can they ever be brought together again? Who can sew the cut?

“I have Kant's entire works to read, leave me alone with your ephemeral nonsense.”

Interview in Italian, Linkiesta, Sep. 12, 2020

In/Half describes the world 25 years from now, where people will be disconnected, Slovenia will be post-war, and Europe will be divided by walls. Which of these things do you think is most likely?

I think that in 25 years, the most likely thing to happen is that we will continue to pursue our short-term interests at the expense of everything else. What this will look like will depend on your short-term interest. If it's survival, the world will become increasingly bleak. If it's a higher salary, it will remain more or less the same place of slow-burning depression, punctuated by flashes of expensive joy. But if your short-term interests are domination, submission, and hatred, the world will continue to be a breeding ground for these primitive fantasies, and you might even find it pleasurable. I am basing this on Murphy’s law.

The novel, on the other hand, wasn't written to predict the future. At a certain point, I wondered what the worst thing that could happen was, apart from a nuclear apocalypse. Division, isolation, lack of access to true knowledge: these were my concerns at the time. I wanted to provide a broad and varied background for my characters, to question what my generation would be like on our fiftieth birthday. Not what the world will be like, but how we will be equipped to face whatever happens, based on the values and knowledge we are growing up with.

The pandemic offered a kind of immediate test of this hypotheses.

The current pandemic offers an excellent example of a particular weakness that has informed much of the book: memory loss, a narrowing of temporal perspective, the formlessness of history. Almost immediately, in the first weeks of quarantine, we began to romanticize the bygone era of a few months ago, when we could go out with friends, to the club, visit our grandparents, get lost in crowds… As if we hadn't just seen billions of living creatures die in the Australian bushfires, as if we weren't constantly under pressure, as if we didn't experience our world as a profoundly imperfect place, each of us striving, in our own way, to change it … And governments said, okay, you can't survive under lockdown, here's some money, and we said, great, thanks, as if there weren't people who didn't have the money to survive even before the lockdowns, but had never received aid, despite a vibrant and powerful economy. There wasn't enough money before, when business was booming, but when everything stopped, suddenly there was enough money for everyone. This only makes sense if we want to keep forgetting things ...

And this is the story of my characters. Each of them has had traumatic experiences and was somehow eager to let go of the old world, thinking that a major global shift would free them from the pain of their past. Unfortunately, it doesn't work that way: some problems are real and can't be eliminated by new technological gadgets, a new profile picture, arguing on Twitter, or deleting all social media and pretending to be free from the past. Some things just require hard work, and if we allow ourselves to be constantly distracted, to allow the cloud and drives to replace our memory, this work will only become more difficult.

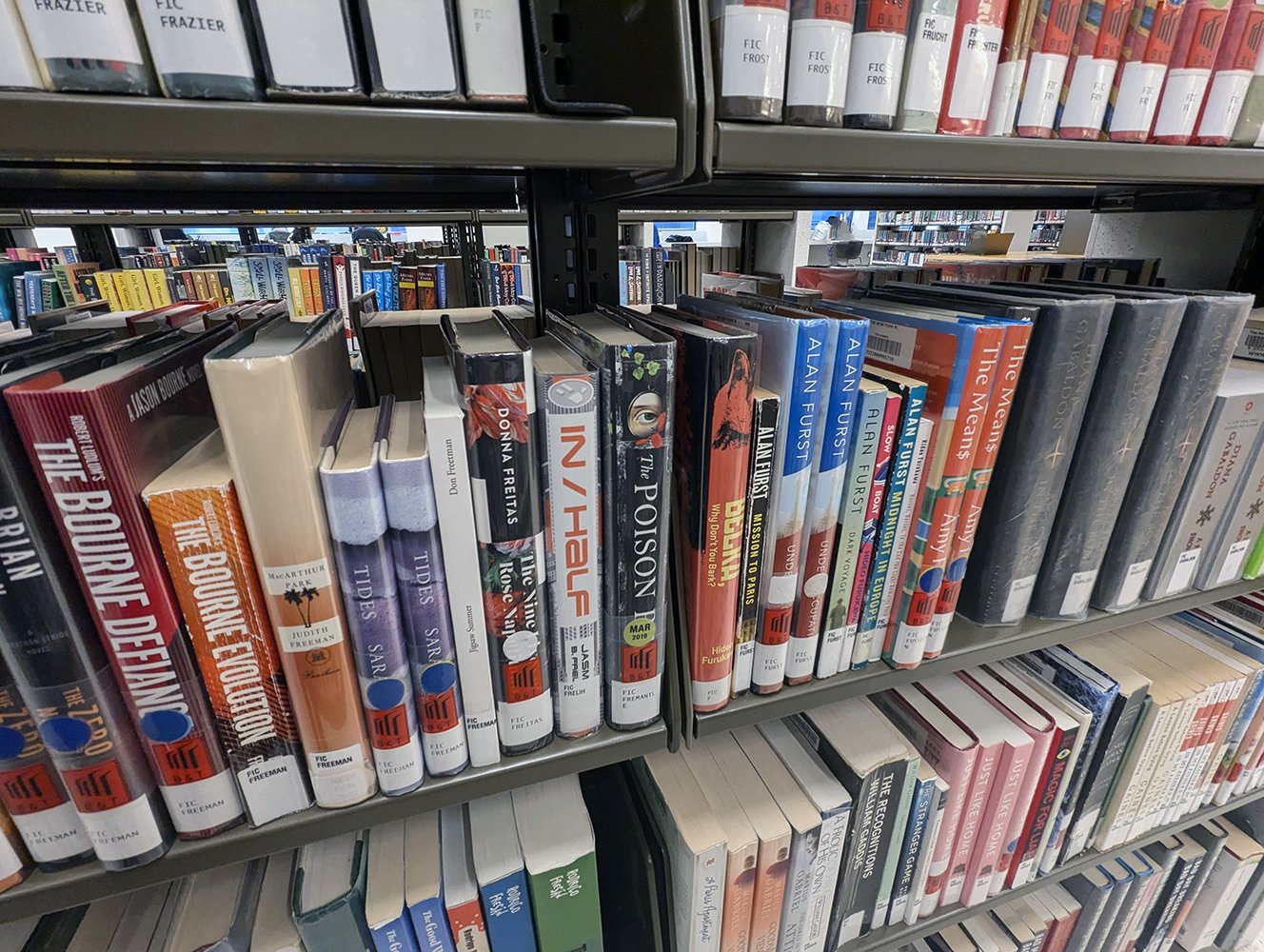

Selected Editions

Na/pol

Cankarjeva založba, Ljubljana, 2013

In/tweeën

De Geus, Amsterdam, 2017

translated by: Roel Schuyt

Na/pola

Ljevak, Zagreb, 2019

translated by: Jagna Pogačnik

Na/pół

Wyszukane, Warszawa, 2020

translated by: Marlena Gruda

A/metà

Safarà, Pordenone, 2021

translated by: Michele Obit

Stē/mesē

Vakxikon, Athens, 2022

translated by: Marianna Avouri